Dos and Don’ts of Machine Learning in Computer Security - Part2

Presentation

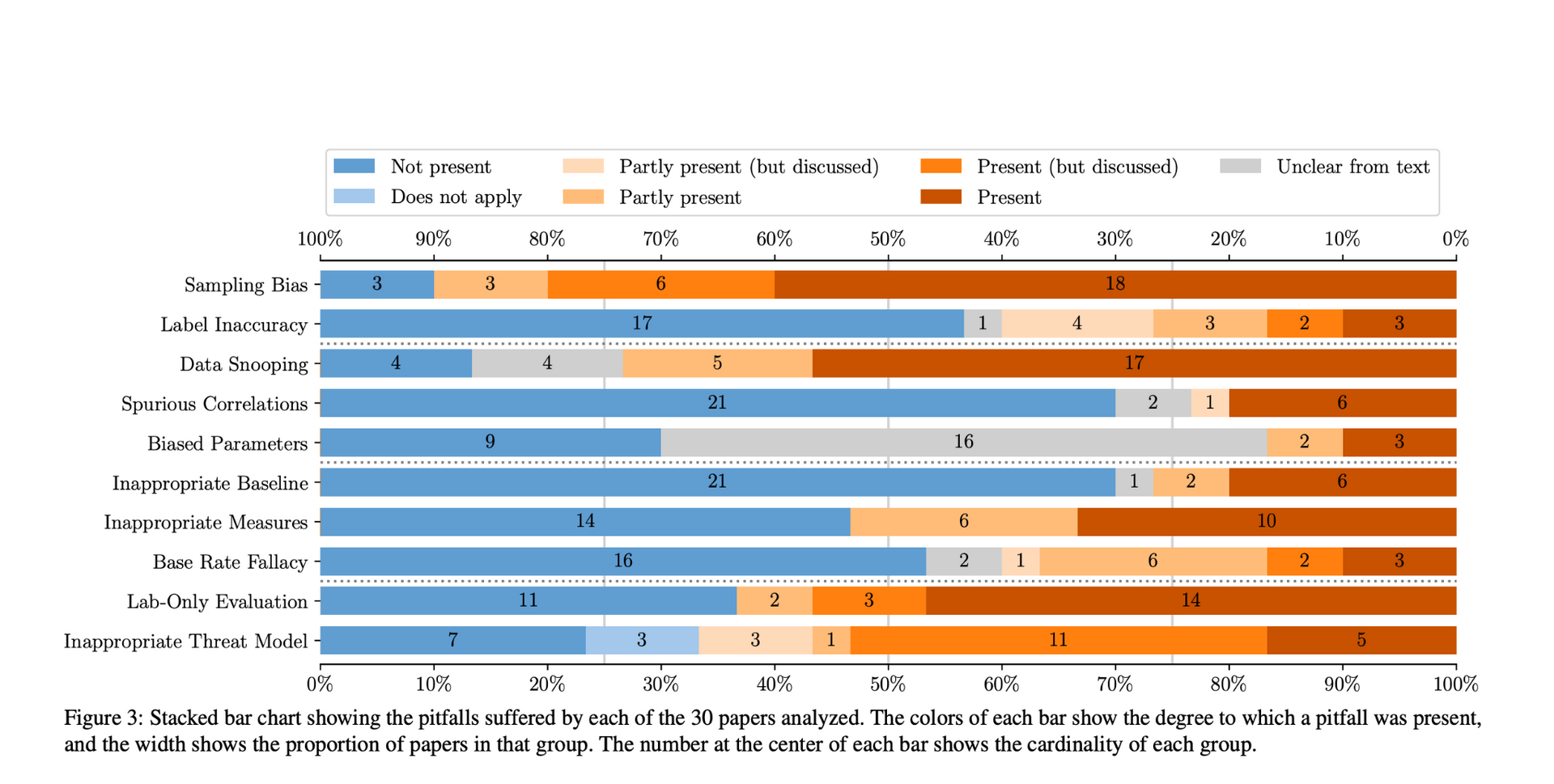

The presentation covered the second part of the paper, focusing on the prevalence of common pitfalls in 30 published papers over the last 10 years at the top 4 security-related conferences. As a review of the first part of the paper, the common pitfalls are listed down below: P1 - Sampling Bias P2 - Label Inaccuracy P3 - Data Snooping P4 - Spurious Correlation P5 - Biased Parameter Selection P6 - Inappropriate Baseline P7 - Inappropriate Performance Measures P8 - Base Rate Fallacy P9 - Lab-Only Evaluation P10 - Inappropriate Threat Model

Each paper was assigned 2 reviewers who checked the presence of pitfalls independently. These independent reviews were combined and the reliability of the reviews was measured using Krippendorff’s alpha.

The following is a graphical representation of the rate at which each pitfall was observed.

The authors of the papers were also contacted for their opinion regarding the results of this study. 98% of the authors who responded were of the opinion that this study would help raise awareness about the pitfalls in this field. 92% of the authors agree that Lab Only Evaluations frequently occur in scientific papers and 46% agree that Base Rate Fallacy could be easily avoided if the authors take a conscious effort to it.

Due to the prevalence of these pitfalls their consequences and impact on different areas of security must also be analyzed.

Mobile Malware Detection

Considering the case of AndroZoo which is one of the most popular Android datasets used by researchers, it was observed that most of the benign applications are from Google Play Store while most of the malicious applications are from Chinese Stores. This peculiarity is an instance of Sampling Bias (P1), and might not be a true representation of the real-world scenario. To test this out, the researchers conducted experiments on two datasets

- D1 - Benign apps are from Google Play Store and Malicious apps are from the Chinese Store (Similar to AndroZoo)

- D2 - Both Benign and Malicious apps are from Google Play Store.

While accuracy was only slightly affected, recall dropped by around 10% from D1 to D2. This also shows the effects of having Inappropriate Performance Measures (P7). Also, it can be inferred that the model has given more importance to the origin of the app rather than the malicious characteristics which is an instance of Spurious Correlations (P4)

Vulnerability Discovery

In the case of machine learning based vulnerability discovery systems, the researchers analyzed a dataset containing source code from National Vulnerability Database and the SARD project. In this dataset, the presence of many artifacts that only belonged to one class was observed, even though they were not directly responsible for any vulnerabilities. This is an instance of spurious correlations and hence models trained on this dataset like the VulDeePecker was observed to fall prey to pitfall P4.

Source Code Author Attribution

Source code Author Attribution is when the model tries to group together source code written by the same author (attribute a source code to a certain author). The dataset used by many of these studies has been from the Google Coding Jam programming competition. However in the competition, since the priority is in solving the challenges as quickly as possible, many contestants reuse personalized template codes. This causes a sampling bias, P1, as this would not be a real-world situation. Also, the style artifacts in this template code (a major proportion of this might be unused code in the template) would be given heavy importance by the model leading to spurious correlations, P4.

Network Intrusion Detection

For Network Intrusion Detection systems, Lab-Only evaluation is one of the most commonly observed pitfalls, P9. Because of the difficulty in collecting real-world attacks, researchers generate synthetic data trying to emulate the real-world environment, which mostly leads to P9. Also, some of the state-of-the-art models (KITSUNE) built on such lab-only environment were shown to be outperformed by boxplots, hence demonstrating a lack of appropriate baseline during evaluations, P6.

Discussion

- One key point of the discussion was that when comparing different models, like it was done in the Mobile Malware Detection to analyze Sampling Bias, the fact that each of these models might be trained with different end goals or priorities in mind. For example, a model that was trained solely on Google Play Store data because it was meant to be deployed in that environment, might not perform well when tested against a different data distribution in the Chinese Stores.

- Getting a representative dataset is not easy, because of the number of contributing factors that go into defining how the real-world data distribution would be. Because of this reason, the researchers are forced to make assumptions about these factors hence causing Sampling Bias in the data they collect. This shows how hard it would be to avoid some pitfalls. So, AV companies would usually be targeting a specific scenario, instead of the entire real-world data distribution.

- The discussion took a tangential path on the difference between malware and vulnerabilities, and how the property of maliciousness lies in intent.

- Another major point of discussion was on Spurious Correlation. It was agreed that the model would be more robust if the features are more directly linked to the causation of the property under detection. However, this is a balance to be struck because attributes that are not directly related to causing maliciousness might also provide valuable information that cannot be discarded. In fact, a lot of AV companies in reality use statistical features like IP ranges to calculate reputation and use this as an initial round of filtering. These features like IP ranges and Operating System would fall under Spurious Correlation but still provides value to the model. However, care must be taken not to depend entirely or heavily on such features.

- Till now the papers presented focused on the techniques of a model detecting malware by comparing it with the information it learned about malware files. There is however a flip-side approach to this, where the model detects or flags files that it does not know or has not encountered in training.